AV Club

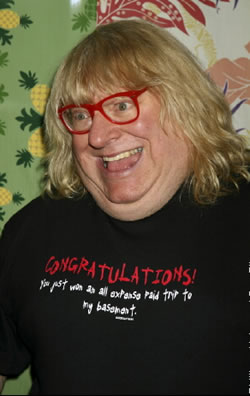

Bruce Vilanch

By Joel Keller February 23, 2011

Frequent appearances on the Whoopi Goldberg-led Hollywood Squares aside, Bruce Vilanch has spent most of his nearly four decades in show business in the writers’ room. The chubby, fuzzy, T-shirt-wearing Vilanch started out writing for ’70s variety shows ranging from The Bette Midler Show to Donny And Marie to the infamously bad Brady Bunch Variety Hour and The Star Wars Holiday Special, but he made his name writing for award shows, the most famous being the Academy Awards. This year marks his 22nd Oscars (airing Sunday at 8 p.m. Eastern on ABC), an impressive feat given the range of hosts who have worked on the show over those years. The A.V. Club recently spoke to Vilanch about the challenge of writing for hosts who aren’t comedians, what he thought of Ricky Gervais’ Golden Globes performance, and why he thinks David Letterman is still sore over the whole “Uma… Oprah†thing.

The A.V. Club: How does writing for Oscar hosts who aren’t comedians challenge you as a writer?

Bruce Vilanch: It’s a different energy. Because when they’re a stand-up, you’ve had time to actually hear their voice, and you know what their rhythm is, and you can write to it. When they’re actors, you’re kind of helping them create a persona, a character they’re going to play on the night. They’re going to play the host of the Academy Awards, and they’re going to bring their own performance chops to it. So it’s quite different, and it changes the energy of the show, too. I like that. I like that we don’t have to come out the first 10 minutes and score, you know, with joke, joke, joke. We can open it in a more novel way and keep playing different pranks as we go through the thing.

AVC: Does it make it easier because it feels like more of a blank slate for you?

BV: Yeah. Well, it does. We’re shaking up a format, which I think is always a good thing. The thing about [2011 Oscar hosts] James [Franco] and Anne [Hathaway] is, they’ve both hosted Saturday Night Live, and they both did a good job at it. So they are accustomed to working with short rehearsal time, and live, lots of pressure, rewrites, things like that. They can make quick changes, which is very advantageous, and they’re skilled comedians. They’re not comics, but they’re comedians, and so they can do things with what they’re given that a comic can’t necessarily do.

AVC: How tough is it to make your jokes sound like Jon Stewart, or Whoopi Goldberg, or Steve Martin?

BV: It’s tough, by God, and I should get paid more money. You know, you have to do homework. You listen to who they are, what they do. I also compare it to designing clothes for people. If somebody brings in Tilda Swinton, you’re not going to give her the same dress you’d give Gabourey Sidibe. Everybody looks different in a different line, a different color. The same thing with the way people speak. I mean, Ellen [DeGeneres]’ attitude is different from Jon Stewart’s attitude is different from Whoopi’s attitude, and you learn what those things are. Now what’s important is that they have an attitude. Everybody has a look, but not everybody has cultivated what their stage persona is. And so when you’re dealing with actors, it just makes it more difficult, because you have to help them come up with one. You know, Johnny Depp has no Johnny Depp character when he’s onstage. You haven’t seen An Evening With Johnny Depp at Carnegie Hall.

AVC: Which host was most challenging for you to write for?

BV: They’re all kind of challenging, but I think it was the dynamic. It was Hugh Jackman, because he’s not a comic, and we had to find a new way to do the show. When Steve Martin and Alec Baldwin were doing it, Steve is a stand-up, Alec isn’t, but he has certainly done that kind of stuff—a lot of Saturday Night Lives, for example. But we had to find ways to use the two of them where they could be who they are, and at the same time, create an energy between the two of them that was unusual. So they’ve all been challenges in one way or another. I mean, Chris Rock, I suppose was the most of a challenge, because he felt himself the most outside show business, the Academy system, that whole world. That’s one reason he was chosen, because the producers want a really fresh slant from a comic, the kind they hadn’t had before.

AVC: How is the dynamic of working with a different writing staff every year?

BV: It varies. I mean, if they’re doing a television show every night like Jon Stewart, or Ellen, or David Letterman, then they have their bunch of people who are sitting on a payroll someplace, who are coming up with material every day of the week. Those are the people who wind up doing the bulk of the work for them when they host the thing, because that’s their team. But when it’s Whoopi, or Billy Crystal, or Steve Martin, who don’t do shows every night—well, Whoopi’s now doing The View every day, but back then, she wasn’t—you get to take charge and start putting together a playbook, and then start writing material for them. You get to be more of the liaison with the host team. You get to be the host team, which is more fun.

AVC: You said in an interview a couple years ago that you were proud of inserting a fart joke in one of Whoopi’s shows. What are some others that went well for you?

BV: I think probably the best example was the year Jack Palance dropped down and gave us push-ups when he accepted his award for supporting actor. Then we got to throw away a lot of the script because we just did Jack Palance jokes, because it was just too delicious, watching this old man carry on like that. Of course, he won his Oscar for Billy Crystal’s movie, and Billy was hosting the show, so Billy could make jokes about him. That was fun. When it was over, we said, “Well, we certainly turned that one around.â€

AVC: What made Billy Crystal a host the Academy wanted to keep going back to over and over and over?

BV: Well, he’s full-service. With Billy, you would get a musical number that was written specially for the occasion. We’ve gotten a film package where we would insert him into things, he would do prop things. He was also a bona fide movie star who could comment from inside, but he had a familiar touch. I mean, part of the reason he was a movie star was because he was a familiar character. He was a guy who you could identify with, and so he was like your entrée into the party. Also he was a big movie star, and that made him a guest at the party that everybody else at the party knew too. It just sort of worked. It didn’t also happen overnight. I mean, he’d hosted about three Grammy awards before that, in which he had sort of cut his teeth on the job. He’d been on the Oscars as a presenter for about five years, so he knew the territory.

AVC: Do you ever wish that, in this era, there was another Bob Hope, or Johnny Carson, or Billy Crystal who could come host the Oscars year after year?

BV: Well, you know, Billy did it eight times. So there has been that. If somebody else were to turn up, that would be great. I mean, I don’t know who would be him, but there are so many more hosts now than there used to be. You know, even when we started the show—one of the challenges when you have a comic hosting the Oscars is to do a joke on the Oscars that has not already been done by David Letterman, Jay Leno, Jimmy Fallon, Craig Ferguson, Joy Behar, Bill Maher, Carson Daly. I mean, there are these guys every night that are coming on and doing stuff. That didn’t used to be that way. It was Hope and there was basically nobody else but Hope. There was Carson and there was nobody else but Carson. So it’s a different world now. It’s not only that, but all these stars are seen every day on ET and Access and Extra, and all of these things… the Inside Edition, Outside Edition, the Underneath Your Edition. So it’s so hard to bring stars on that people haven’t seen, or don’t get access to all the time. The challenge is to come up with stuff that’s interesting in spite of all that.

AVC: Do you look at the day-after reviews of the Oscars?

BV: Oh sure. I mean, I have them framed. I have one rave New York Times review framed next to a flop Los Angeles Times review. And it’s for the same show. These people watched the same show. That’s what happens. They love it, they hate it.

AVC: Which show was it?

BV: It was a Whoopi show. It was the Whoopi show that Quincy Jones produced [in 1996]. The L.A. Times said the ayatollah should come after Vilanch with a fatwa. It was like that. I said, “Well, that’s kind of severe. That’s a bit harsh.†But then they fired him. So the critic got fired, so I thought, “Okay, The karma wagon has backed up over your feet!â€

AVC: When you read reviews that say a host like Rock or Stewart didn’t go far enough, or that they were tentative, what do you usually think?

BV: I agree. I mean, people who watch Jon Stewart’s show every night don’t think he went far enough, because he couldn’t do what he does on his show every night, because it’s a different job. The same thing with Chris Rock. He can’t come out and do a tossed-salad routine, the way he does on his HBO shows, because this is the Academy Awards. So people who tune in to see that are going to be disappointed. Everybody else, who doesn’t necessarily know what [the host] does, can wind up falling in love with him, because he’s taking a different tack, and they’re seeing him fresh for the first time. It can go either way. So I understand what that’s about. I mean, there’s a job you have, and you can’t necessarily bring your other job to it. Johnny Carson famously told Letterman that he never did Carnac on the Oscar show. Because, you know, Letterman brought on a spinning dog, and I think he was giving away a car, there are a couple of Letterman-esque things, the Top 10 list and all that, which he might not have needed to bring on, because it was a different gig.

AVC: Letterman still jokes about his hosting gig 16 years later.

BV: I know. He won’t let go.

AVC: He still seems to harbor some sort of lingering disappointment over how that went down.

BV: I think he probably harbors lingering disappointment over a prom date. I mean, he’s not one of the most lighthearted people. Although since he’s had the heart attack and the kid, he certainly has gotten happier. Listen, they asked him to host the following year, and he said no. He didn’t ever want to go back, and he has made it an anchor of his shtick ever since. In fact, two years later, when Billy came back and we put a film package together, we had him in a parody of The English Patient saying “Billy, just say Uma… Oprah, Uma… Oprah,†and then machine-gunning him down on the beach. And Letterman said yes. We didn’t even have to finish the pitch. He said, “I’m doing it.†He loves to make fun of himself.

AVC: As the person who helped bring that to life, how do you feel about that?

BV: Rob Burnett, who is his producer now, is the proud author of “Uma… Oprah,†and it’ll probably be the title of his memoirs: Uma… Oprah by Rob Burnett. I actually told him not to do it. I said I thought it was a bad idea, I said, “These two people are sitting out there. Uma Thurman’s been nominated for an Oscar, and her world could change overnight. She doesn’t need TV Boy making jokes about her.†He nodded, and he went ahead and did it anyway. But he had a lot of stronger material that year that he didn’t use. I don’t know why. But you know, Dave is also somebody who likes to come in with sabers, you know. A joke doesn’t work, and then he’ll make fun of it. Like Carson, actually. Carson did the same thing.

AVC: And he likes to hammer jokes to death, even if they’re not the funniest thing, if they amuse him.

BV: And something he still does, which absolutely, I marvel that he can get away with this, you know, he does his own warm-up. I mean, he’ll come out and talk to the studio audience before the show, then he goes backstage, and they bring him out again on camera, live. And he will do a joke that’s a reference to something only the studio audience has heard. The audience at home has no idea what he’s talking about. The audience in the studio cracks up, goes ballistic. They’ll go to a reaction shot of the woman he’s talking about. We have no idea what he’s doing. You’d think somebody would say to him, “Dave, that’s playing to 400 people, and there are 4 million people who were sitting there at home with their thumbs up their noses, going whaaaaat?†It doesn’t seem to bother him.

AVC: When you watched Ricky Gervais at the Golden Globes, and you saw that he actually didn’t play it safe, did you think, “He’s going to get in trouble for his performance?â€

BV: Of course he was. I mean, he never hit funny. Making jokes about The Tourist is just not funny; it’s just kind of mean-spirited and cruel. I think that partially is that he lost his cuddly—he was heavier and befuddled and kind of looked a bit lost [last year], and this year, he came out and he was like a shark. He took his jacket off, and his body’s all worked out, and it’s not a sympathetic character up there. He was just a mean kind of player. Plus, I thought his targets were lame. I mean, Charlie Sheen and how old Bruce Willis is? I mean, this is old stuff. Scientology and who’s gay and who’s not? This is not fresh target material to make jokes about. All you can be is outrageous—you’re not going to be funny. All you’re going to get is a lot of “oooooohhhhh.†And that’s what he got. He got a lot of “oooooohhhhs.â€

AVC: But do you think that hosts are in a no-win situation sometimes, given who they’re playing to in the theater, as opposed to who they’re playing to on TV?

BV: I think sometimes. I don’t think he was in that, but I do think sometimes it happens. As I’m always fond of telling hosts at the Oscars who are doing it for their first time, for everybody who wins, there are four people who don’t. As the evening wears on, the room fills up with losers, and then they are bitter. They are not interested in any joke you have to say; they just want to get to the bar, or they want to get to their phone so they can begin firing people. It’s unfortunate. You feel the air go out of the room as the evening wears on, because a lot of the people who were there came with very high hopes, and they no longer have them. This is not the case with the Golden Globes, because they’re sitting at tables drinking wine, so it’s a different kind of situation. Nothing much is riding on whether you win a Golden Globe.

AVC: Do you wish they’d serve more alcohol at the Oscars?

BV: Absolutely. Yeah. I mean, that’s my fervent desire, especially backstage. But probably, they want to maintain a certain level of decorum, unlike the Golden Globes, where the sloppier it gets, the better it is.

AVC: As the nominated movies have gotten smaller, how tough has it gotten to write jokes about them? How are you going to do jokes about Winter’s Bone, for instance?

BV: Well, first of all, we don’t have a comic who needs to make joke about that. So if we do, it’ll be in some other context. Had we had a comic, we probably would have made a joke about the fact that nobody’s seen it. The first time we did the Billy Crystal movie [the clip reel at the beginning of the show], we did it because The English Patient was the big picture. Jerry Maguire was the only movie people had seen, so we said, “And here are the nominees: Tom Cruise and a bunch of other guys.†Because nobody knew who Brenda Blethyn was, or Marianne Jean-Baptiste. I mean, these were the nominees. These were the big nominees. And it was kind of amazing. The biggest picture that year had been the first reissue of Star Wars. So we created a movie, which we bookended with Star Wars, with Billy as Yoda, and then we went into all the other movies that had been nominated that year. Had we known The English Patient was going to win nine Oscars—which still staggers people, because when people ask me what’s the trial of the century, I say The English Patient—we might have made more jokes about it. But we didn’t know at that time.

To me, the funniest line of the night was when Andrew Lloyd Webber won an Oscar for writing a song for Evita, and he said, “Thank God The English Patient had no songs. Because it won everything.†That was why we did that movie with Billy Crystal, because we felt that so many people hadn’t seen the movies. They were great movies, like Fargo and Secrets And Lies. But Jerry Maguire was the only big-box-office picture that year. And you know, part of the reason the Oscars has opened up the Best Picture category to 10 is because they want more of a spectrum. There were a lot of little movies people hadn’t heard of, and a couple of big box-office pictures like The Dark Knight didn’t get nominated because there wasn’t room for it, because the Academy liked the little pictures. So now, this is the second year of the 10 Best Pictures. The range is really pretty amazing to me. When you go from Toy Story 3 to Winter’s Bone, I mean, that’s quite an impressive range. I mean, last year, Avatar, the biggest picture of all time, lost to The Hurt Locker. But there were like eight other movies that were also equally well represented, that represented every different spectrum of the movie business.

AVC: So how do you take a fresh angle on a movie that has infiltrated pop culture to the point where the jokes, like the ones that say Inception is confusing, are getting old?

BV: Well, you know, you try and do something different. I mean, if I had my way, I was going to have the accountant come out to explain Inception. You know, the Price Waterhouse people, and in Price Waterhouse language. But here we are with a show that people are always bitching is too long, and I thought “Do we really want to spend three minutes on this joke?†And if Inception was the runaway favorite, maybe it would be worth it. But it isn’t. There are nine other pictures that are equally likely or unlikely to win. But you’d have to do something like that, because you’d have to find some way that was unique, that wasn’t just another Inception confusion joke, some other angle. That’s just one that came to me a while back, but I knew it’d never make it.

AVC: How do you approach a movie like Schindler’s List or The Hurt Locker, that has such tough subject matter that making jokes about it would be inappropriate?

BV: Sometimes you just skip over it. You just go for the ones you can make jokes about. We couldn’t make any jokes about Precious last year, because, you know, people don’t seem to find rape amusing. I wanted Steve and Alec last year to come out wearing sweatshirts, one said “Team Precious,†the other said “Team Mama.†But you’d have to know the Twilight thing, and you’d have to know the Precious thing. We had a joke: “Precious is about a girl who’s raped by her father twice. Who says men can’t commit?†Now you see, now that’s a funny joke, except you have to go with the notion that you can make any kind of a joke about rape.

AVC: I’m guessing that joke didn’t come close to making it.

BV: Right, and most people think you cannot, and I understand that. But I mean, you know, there we were, coming up with those kinds of jokes, and finally we just said, “You know what? Let’s just leave Precious alone.†The only joke, I don’t even know if we made anything, but we were down to making jokes about the weird title. Precious, From The Novel Push By Sapphire, you know, which was like three random people. Push, Sapphire, and Precious—are those the Pips? Who are they?

AVC: When you look at each nominated movie, are you looking for that one thing you can latch onto?

BV: That’s exactly what you do: You look and see what’s unique about each movie. When we first sat down, we just said “How many ballerina jokes [for Black Swan], how many arm-cutting jokes [for 127 Hours], how many things can we do? Or can we ignore them?†But it’s hard to ignore, you know, a girl who turns into a black chicken. I mean, it’s really difficult. I could say, “I want to have Ernest Borgnine come in a black swan outfit, just sitting in the audience and just have him run on the stage, Kanye-like, and interrupt somebody.†But I mean, that’s what you come down to. When you do a thing like Inception, it’s very hard, because all those Inception things are great big special effects. They’re time-consuming and they’re tough to do, yeah. I would love to freeze the show and keep going back to the same people falling off a cliff in a Volkswagen minibus 17 times. It just adds time to the whole thing.

AVC: What was the bigger nightmare to write for: The Star Wars Holiday Special or the Brady Bunch Variety Hour?

BV: Well, you know, The Brady Bunch was about seven people who could not sing or dance, and they had to do both. We called it One Tenille And Seven Captains, which was something of an old reference. But nothing will ever equal the Star Wars Holiday Special, I have to say. I mean, The Brady Bunch, there’ve been several iterations of that, but nobody involved with The Brady Bunch has ever tried to buy up every copy of it. Unlike George Lucas, who was like on a personal extermination program of getting every single copy of The Star Wars Holiday Special and literally presiding over the molecular breakdown of every single one.

AVC: Yeah, but Robert Reed as a song-and-dance man doesn’t sound like something he would be proud of.

BV: Something to behold, it was. And we put him in drag a lot. But I put him in drag a lot because Woody Allen had written the Garry Moore Show. Garry Moore was not a very funny guy, and he had a psychic named Durward Kirby who wasn’t very funny, and Woody Allen had to write for them. Every sketch he wrote, at the top of the page, he would say, “Durward and Garry enter wearing dresses.†Of course they wouldn’t do it, and when the sketch bombed, he said “Well, they wouldn’t wear the dresses. It’s right there on the top of the page.†So it was kind of like the same feeling. It’s like no matter what, “Put [Reed] in a dress! He will get a laugh, trust me.†So we went all around town finding everybody else’s Carmen Miranda drag. You know, any tall person who ever did Carmen Miranda, we rented the costume, because we wanted to do that, to dress him up. And it worked!

AVC: It did work for what, the nine weeks it was on?

BV: But, you know, once the Brady Bunch movies came out, much later, the parody movies, Paramount sold off all the Brady Bunch variety shows to Nickelodeon, and they were showing them on Nick At Nite—Nick At Nightmare, I called it. My stoned friends would call me at 2 o’clock in the morning and they would say, “Dude, you’re on Nickelodeon! Your name’s on this show, dude, and this guy Mr. Brady’s dancing and he’s in a ballgown, and it’s just, it’s so trippy.â€

AVC: It must’ve been trippy to work on it.

BV: Oh yes. Well, it was the ’70s. We were chemically altered.