The Advocate

Bruce Vilanch dishes on staples of the 1970s, Paul Lynde, the Brady Bunch, Charo, and more

By John Casey

January 8, 2025

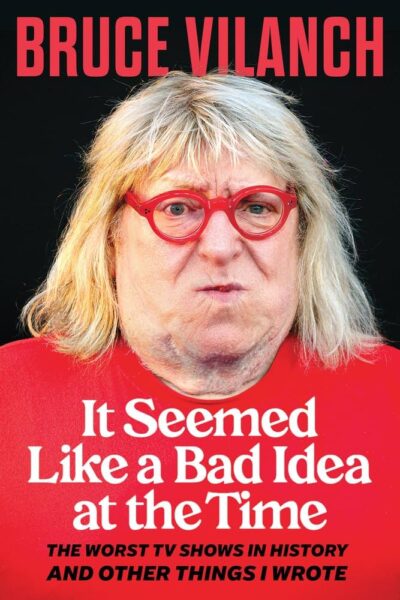

His new book, It Seemed Like a Bad Idea at the Time, talks about his work on TV’s worst shows ever that are now cult classics. Pre-Order Here

Bruce Vilanch is a queer man whose wit has defined decades of showbiz, and he’s out with a hilarious new memoir, It Seemed Like a Bad Idea at the Time. The book delves into part of his rollicking career, recounting some of the flops that he worked on, primarily in the 1970s, that have found a new audience on YouTube, perhaps the most infamous being 1978’s The Star Wars Holiday Special, which is usually ranked as the worst TV show ever made.

Vilanch’s storytelling in the book is both uproarious and reflective, offering insights into an entertainment industry that often tiptoed the line between brilliance and absurdity.

From the beginning of his career, Bruce Vilanch has been an out and proud member of the LGBTQ+ community, “You sought out other gay people, and they saw you out,” he recalls. “There was always a layer of homophobia going on. I mean, there were people who were afraid of gay people. And I said, I don’t want to work for anybody who’s like that. Given the choice, I’m not going to change myself, and so I passed up a few things. I’m sure I was passed over for work because they weren’t comfortable with me.”

His multifaceted work includes stints as a writer and actor. His credits span an impressive array of awards shows, 25 Academy Award telecasts among them, earning him two writing Emmys among seven nominations. He has penned dialogue for icons like Cher, disco hits for Eartha Kitt and the Village People, and a variety of TV spectacles that remain unforgettable, whether celebrated or cringeworthy. Vilanch also used to write for The Advocate.

At the heart of Vilanch’s memoir are tales from the 1970s, a decade when variety television reigned supreme and creativity often collided with chaos. “The impetus for the book,” Vilanch explains, “came from being on a lot of podcasts during COVID, with younger people asking about these pieces of … well, let’s call them ‘television history.’ “Shows like The Star Wars Holiday Special, The Brady Bunch Hour, and The Paul Lynde Halloween Special have taken on a second life on YouTube, and people always ask the same question: How did this happen? And have the people responsible paid their debt to society?”

Vilanch’s work with Lynde, a closeted gay man, offers a fascinating glimpse into the intersection of talent and tragedy. Lynde, known for his razor-sharp humor and camp sensibility, remains a complex figure in Vilanch’s memory. “Paul really thought what he was doing was insignificant,” Vilanch remembers. “Compared to his contemporaries like Woody Allen or Mel Brooks, he felt like he had nothing that would last forever. Ironically, The Paul Lynde Halloween Special did exactly that. It’s a cult classic now, but not for the reasons Paul might have wanted.”

Featuring Lynde, the rock group Kiss, and an ensemble of eccentric guest stars, the special earned decent ratings upon release but was dismissed by many as so-bad-it’s-good. “If Paul knew people would still be talking about it decades later, he’d be spinning in his grave,” Vilanch jokes.

Vilanch remembers Lynde as deeply charming and acerbic, albeit guarded and troubled. “He could be hilarious and warm after one drink, but after two, something totally mean and different came out that reflected his darker moods,” Vilanch said.

And Vilanch had another experience with another gay actor who could also be moody. By the time Vilanch joined The Brady Bunch Hour, Robert Reed, who played the beloved patriarch Mike Brady, had already become a surrogate father figure to the cast. “Bob was very protective of the kids, especially since many came from situations where they were treated as revenue streams,” Vilanch says.

Reed’s private life added another layer of complexity. “His was a closely guarded secret,” Vilanch recalls. “He was terrified of being outed. It would have ended his career as a leading man. But his dedication to the kids and the show was undeniable. That was another reason he kept his sexuality hidden. He thought it would disappoint the kids.”

As for the variety show itself, Vilanch has a rocky metaphor: “It was destined to hit the iceberg. Fundamentally flawed, but somehow, people are still talking about it.”

Vilanch also spent time writing for the Donny and Marie show,a cultural collision of wholesomeness and subversive subtext. “So much of the production crew was gay,” Vilanch says. “Yet here were Donny and Marie, squeaky-clean Mormons. And during production, the hairdresser contracted hepatitis and we were all required to get a shot.”

The juxtaposition wasn’t lost on Marie Osmond, whom Vilanch recalls as sharp and self-aware, even in her youth. “She once joked to me, ‘Why is it always the hairdresser?’ when her stylist got hepatitis,” he remembered with a laugh. “But at that time, gay men were mostly identified by stereotypes, even though several members of the ‘masculine’ crew were gay, and there was a butch lesbian.”

The dynamic between the Osmonds and their largely queer production team created a fascinating environment. “It was the era where people didn’t talk openly about being gay,” Vilanch explains. “But within the show’s ecosystem, everyone just made it work.”

Another highlight of Vilanch’s career was writing for Charo, the flamboyant Spanish entertainer known for her “cuchi-cuchi” catchphrase. “Charo was a shrewd, sweet woman who knew exactly what she was doing,” Vilanch says. “She was riffing off Carmen Miranda, but she made it her own. Even at her age now, she still plays into her persona, though she’s strategically costumed, let’s say.”

Charo’s humor and larger-than-life personality made her a staple of ‘70s and ‘80s television, including 10 appearances on The Love Boat. Vilanch fondly recalls her appeal, especially to gay audiences, saying, “She’s beloved on gay cruises. She knows her audience and leans into it beautifully.”

Vilanch’s memoir doesn’t just dish out hilarity — it also offers a poignant reflection on resilience in the face of adversity. As an out gay writer in a notoriously homophobic industry, Vilanch had to chart his own course. “I wasn’t going to let who I was get in my way,” he says. “If someone didn’t want to work with me, that was their loss.”

In true Vilanch fashion, the book serves as a reminder that even the most outrageous misfires can become cultural touchstones, and that sometimes, the best ideas really do start as bad ones.

His multifaceted work includes stints as a writer and actor. His credits span an impressive array of awards shows, 25 Academy Award telecasts among them, earning him two writing Emmys among seven nominations. He has penned dialogue for icons like Cher, disco hits for Eartha Kitt and the Village People, and a variety of TV spectacles that remain unforgettable, whether celebrated or cringeworthy. Vilanch also used to write for The Advocate.

At the heart of Vilanch’s memoir are tales from the 1970s, a decade when variety television reigned supreme and creativity often collided with chaos. “The impetus for the book,” Vilanch explains, “came from being on a lot of podcasts during COVID, with younger people asking about these pieces of … well, let’s call them ‘television history.’ “Shows like The Star Wars Holiday Special, The Brady Bunch Hour, and The Paul Lynde Halloween Special have taken on a second life on YouTube, and people always ask the same question: How did this happen? And have the people responsible paid their debt to society?”

Vilanch’s work with Lynde, a closeted gay man, offers a fascinating glimpse into the intersection of talent and tragedy. Lynde, known for his razor-sharp humor and camp sensibility, remains a complex figure in Vilanch’s memory. “Paul really thought what he was doing was insignificant,” Vilanch remembers. “Compared to his contemporaries like Woody Allen or Mel Brooks, he felt like he had nothing that would last forever. Ironically, The Paul Lynde Halloween Special did exactly that. It’s a cult classic now, but not for the reasons Paul might have wanted.”

Featuring Lynde, the rock group Kiss, and an ensemble of eccentric guest stars, the special earned decent ratings upon release but was dismissed by many as so-bad-it’s-good. “If Paul knew people would still be talking about it decades later, he’d be spinning in his grave,” Vilanch jokes.

Vilanch remembers Lynde as deeply charming and acerbic, albeit guarded and troubled. “He could be hilarious and warm after one drink, but after two, something mean and different came out that reflected his darker moods,” Vilanch said.

And Vilanch had another experience with another gay actor who could also be moody. By the time Vilanch joined The Brady Bunch Hour, Robert Reed, who played the beloved patriarch Mike Brady, had already become a surrogate father figure to the cast. “Bob was very protective of the kids, especially since many came from situations where they were treated as revenue streams,” Vilanch syas.

Reed’s private life added another layer of complexity. “His was a closely guarded secret,” Vilanch recalls. “He was terrified of being outed. It would have ended his career as a leading man. But his dedication to the kids and the show was undeniable. That was another reason he kept his sexuality hidden. He thought it would disappoint the kids.”

Vilanch uses a rocky metaphor for the variety show itself: “It was destined to hit the iceberg. Fundamentally flawed, but somehow, people are still talking about it.”

Vilanch also spent time writing for the Donny and Marie show,a cultural collision of wholesomeness and subversive subtext. “So much of the production crew was gay,” Vilanch says. “Yet here were Donny and Marie, squeaky-clean Mormons. And during production, the hairdresser contracted hepatitis and we were all required to get a shot.”

The juxtaposition wasn’t lost on Marie Osmond, whom Vilanch recalls as sharp and self-aware, even in her youth. “She once joked to me, ‘Why is it always the hairdresser?’ when her stylist got hepatitis,” he remembered with a laugh. “But at that time, gay men were mostly identified by stereotypes, even though several members of the ‘masculine’ crew were gay, and there was a butch lesbian.”

The dynamic between the Osmonds and their predominantly queer production team created a fascinating environment. “It was the era where people didn’t talk openly about being gay,” Vilanch explains. “But everyone just made it work within the show’s ecosystem.”

Another highlight of Vilanch’s career was writing for Charo, the flamboyant Spanish entertainer known for her “cuchi-cuchi” catchphrase. “Charo was a shrewd, sweet woman who knew exactly what she was doing,” Vilanch says. “She was riffing off Carmen Miranda but made it her own. Even at her age now, she still plays into her persona, though she’s strategically costumed, let’s say.”

Charo’s humor and larger-than-life personality made her a staple of ‘70s and ‘80s television, including 10 appearances on The Love Boat. Vilanch fondly recalls her appeal, especially to gay audiences, saying, “She’s beloved on gay cruises. She knows her audience and leans into it beautifully.”

Vilanch’s memoir doesn’t just dish out hilarity — it also offers a poignant reflection on resilience in the face of adversity. As an out gay writer in a notoriously homophobic industry, Vilanch had to chart his course. “I wasn’t going to let who I was get in my way,” he says. “If someone didn’t want to work with me, that was their loss.”

In true Vilanch fashion, the book serves as a reminder that even the most outrageous misfires can become cultural touchstones and that sometimes, the best ideas do start as bad ones.